ASIATIC CHOLERA

First Cholera Pandemic 1816-1826

Cholera started in India in 1817.

Second Pandemic 1829-1851

The second pandemic spread from Bengal in 1826. It took three years to reach Persia and Afghanistan, and from there followed the caravan routes to Orenburg in the south-east corner of European Russia. Early in 1830, after a winter's respite, it began its apparently inexorable advance which in the next three years took it through the whole of Eastern Europe, Austria, Germany, Great Britain and France to the Americas and East and North Africa. In its wake it left hundreds of thousands of deaths, sheer blind panic and widespread riots and revolts. As it spread from Russia to Germany and the Baltic States in June 1831, its progress was viewed in England with increasing disquiet.

When cholera did break out in Sunderland in September 1831, (a keelman, William Sproat, was the first case), it did not spread rapidly. Initial panic subsided as the disease took three months to cover the Tyne/Tees area. (It made one surprising long-distance sprint to Haddington near Edinburgh in December). But general alarm returned with the virulent outbreak of cholera in Gateshead on 26th December 1831, and with its appearance in the dock area of London in February 1832. From then on, with the exception of a few weeks in May, it spread widely and swiftly, until by November 1832 it had radiated throughout the length and breadth of Britain. Altogether it appeared in 431 towns and villages, affecting 82,528 people and killing 31,376. It caused great alarm and widespread fear wherever it went, coincided (to the government's obvious alarm) with the agitation for the Reform Bill, and exacerbated social tensions at a critical moment.

Accurate statistics for the 1832 Cholera epidemic in Wales are not available since the Registrar-General's Department was not established until after that date, its first annual report being issued in the year 1839. Creighton gave the following mortality figures for Cholera in Monmouthshire during 1832-33 epidemic: Deaths in Newport 13; Abergavenny 2.

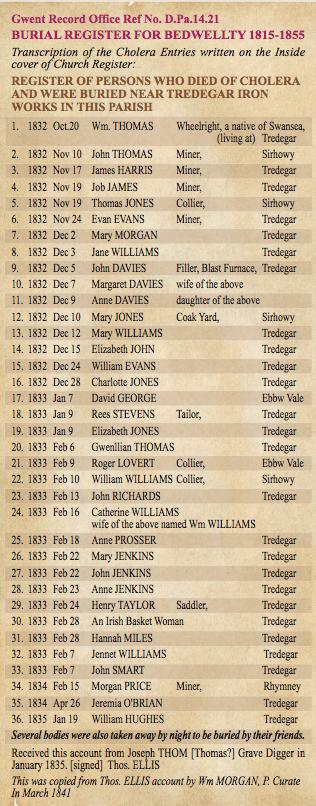

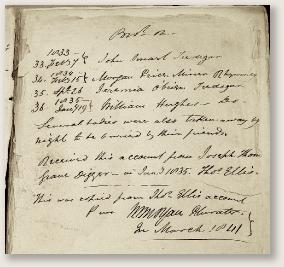

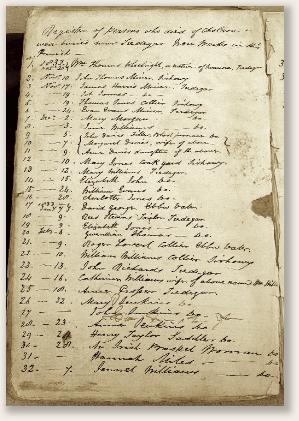

Cholera in Tredegar

The first major cholera epidemic to strike Tredegar was in 1832-33. This outbreak was part of a world wide pandemic that arrived in England in October 1831. A more serious one followed in 1849 in London where it took over 14,000 lives. It was twice as bad as the outbreak in the 1830s in England and it was also worse in Cefn Golau. By July 1849 the disease had reached Rhymney and then Nantyglo in August, and then moved on to Tredegar. Scarcely a street in Tredegar remained unaffected. Those infected appeared to be well in the morning but were dead by nightfall. The doctors searched for remedies without success, people left their homes and fled into the countryside while others stayed indoors. Many sought help from their religion and the chapels were packed, but the death toll still mounted. People could appear to be fit in the morning and then be dead by evening. The disease caused so much fear that few people were willing to help bury the victims. With the arrival of colder and wetter weather in the autumn, the number of new infections gradually dwindled. This outbreak killed 52,000 people in England and Wales. There was also a smaller outbreak in 1866.

Cefn Golau is a disused cholera cemetery situated on a narrow mountain ridge in the county borough of Blaenau Gwent, and located between Rhymney and Tredegar in south-east Wales. A suburb of Tredegar and a nearby feeder reservoir (or pond) have the same name. The graves date from 1832 to 1855 with many for August and September 1849

The cemetery is a Scheduled Ancient Monument. The headstones dating from 1832 are few in number, small, with boldly cut scripts and elegant floral designs. The stones from the 1849 outbreak are much larger and more numerous, with most of the deaths dating from the months of August and September when the epidemic was at its peak. There is a single stone dated 1866 when the third outbreak took place - this was the smallest and the last in the area.

This burial ground on its remote windswept site has long been abandoned but a few gravestones still stand in the sheep-nibbled turf. One is a memorial to Thomas James, who died on 18 August 1849, aged 24 years. The inscription reads:

- One night and day I bore great pain,

- To try for cure was all in vain,

- But God knew what to me was best,

- Did ease my pain and give me rest

Some of the gravestones are in English, others in Welsh and some are in a mixture of the two languages

Symptoms of the disease:

In the 19th Century Cholera had no known cure, although it was soon common knowledge that it frequently killed its victims within three hours of onset. The symptoms were acute. Cholera began with giddiness, a sick stomach, nervous agitation, intermittent pulse, and cramps in the extremities which rapidly moved to the trunk. Then followed acute vomiting and purging of fluid like rice water. The features contracted and the eyes sank, leaving an expression of terror and wildness. The whole surface of the body had a leaden blue, black or deep brown tint, varying in shade with the intensity of the attack. The fingers and toes were reduced in size, the skin became wrinkled and folded, while the pulse virtually disappeared. The skin was cold and clammy, while the tongue remained moist 'but flabby and chilled like a piece of dead fish'. Respiration became irregular, rigid spasms occurred in the legs and arms, and the secretion of urine was totally suspended. At this stage the patient fell into a coma from which he virtually never recovered.

1848-1850: a two-year outbreak in England & Wales claimed 52,000 lives. In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city's history, claiming 14,137 lives, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever. In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool, an embarkation point for immigrants to North America, and 1,834 in Hull.

The first case of cholera in Wales in this second epidemic appeared on 13 May 1849 in Cardiff, and in the subsequent months the disease made enormous ravages in the South Wales valleys.

Figures vary enormously for mortality in Monmouthshire:

Deaths in Tredegar 157 (or 203); Aberystruth 210 (or 223); Abergavenny 9; Pontypool 61; and Newport 209 (or 246)

Third Pandemic 1852-1860

1853–1854: In Britain as a whole this epidemic resulted in 15,000 deaths; in London it claimed 10,738 lives. The Soho outbreak in London ended after the physician John Snow identified a neighbourhood Broad Street pump as contaminated and convinced officials to remove its handle. John Snow had used statistics in dealing with aspects of the use of Chloroform in surgery and Childbirth and its dangers, and when Cholera arrived in London he used his influence to obtain addresses of those who died of cholera, and investigated first an outbreak in the Soho area, and then one in Deptford. His most well-known influential study, of the area around the water pump in Broad Street, Soho, was first published in a letter ‘The Cholera Near Golden Square, and at Deptford’ by John Snow, Medical Times and Gazette 9: 321-22, September 23, 1854. In it he concluded forcefully ‘The result of this inquiry, then, is, that there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump-well.’ Further ‘The pump-well in Broad Street is from 28 to 30 feet in depth, and the sewer, which passes a few yards from it, is 22 feet below the surface. This sewer proceeds from Marshall-street, where some cases of cholera had occurred before the great outbreak. I am of opinion that the contamination of the water of the pump-wells of large towns is a matter of vital importance. Most of the pumps in this neighbourhood yield water that is very impure and I believe that it is merely to the accident of the cholera evacuations not having passed along the sewers nearest to the wells that many localities in London near a favourite pump have escaped a catastrophe similar to that which has just occurred in this parish’.

Fourth Pandemic 1853-1875

June 1866, a localised epidemic in the East End of London claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems; the East End section was not quite complete. William Farr, using the work of John Snow, as to contaminated drinking water being the likely source of the disease, relatively quickly identified the East London Water Company as the source of the contaminated water. Quick action prevented further deaths.

Also in 1866 a minor outbreak occurred in South Wales. In the Monmouthshire area there were 61 deaths in Newport and 122 deaths in Bedwellty.

Fifth Pandemic 1881-1896

This was the last serious European cholera outbreak as cities improved their sanitation and water systems.

............

Review of the work of John Snow's "On the Mode of Communication of Cholera."

Member of the Royal College of Physicians, &c.

2nd Edition, much enlarged. 8vo. Pp.162. London: 1855.

A person suffering from cholera, being carried into a locality where no cholera previously existed, may be the medium of exciting an outbreak of the disease. The evidence on this point is pretty conclusive.

But how does cholera spread from individual to individual? The generally received opinion is, that a something is emitted from the sick which contaminates the air around, and then the healthy inhaling that air are infected with the disease.

Dr. Snow is an opponent of this opinion. He maintains that whenever cholera spreads from individual to individual, it does so in consequence of the healthy swallowing more or less of the alimentary excreta of the sick; and he maintains further, that the ordinary mode in which these excreta are carried to the healthy, is through the medium of water used for ordinary beverage. Dr. Snow has taken infinite pains to establish the doctrine he has propounded; and, although he now and then shows by his reasoning that he is more than a little prejudiced in favour of his own notion, yet he advances facts enough,— facts, too, very numerous, and very carefully observed,—to prove to the most sceptical, that the water-supply is one of the most efficient agents in determining the occurrence of an outbreak of cholera. Believing Dr. Snow's work to be one of the most important which has yet been published on Cholera, we shall offer our readers a pretty full abstract of it, taking care especially to point out the kind of proof which he offers in support of his theory.

Dr. Snow first shows that the circumstances known to be favourable to the spread of cholera are those which afford the greatest facilities for the ingestion of the cholera ejections and dejections by friends and neighbours of the sick. Want of personal cleanliness, and deficiency of light, by favouring this, are among the most commonly admitted determining causes of cholera.

The bed linen nearly always becomes wetted by the cholera evacuations; and, as these are devoid of colour and odour, the hands of persons waiting on the patient become soiled without their knowing it. "Supposing, as is the case in the houses of the poor, these persons cook and handle the food of the other members of the household, then the cholera evacuations may be administered to several in the same family." Hence the thousands of instances in which, among this class of the population, a case of cholera in one member of the family is followed by other cases; while medical men and others, who merely visit the patients, generally escape.

The post-mortem inspection of those dead from cholera, is rarely if ever followed by the disease. Medical men are careful, under these circumstances, to wash their hands. Women engaged in laying out the dead often suffer; as a class, they are not remarkable for performing frequent ablutions. Those again "who attend the funeral, and have no connexion with the body, frequently contract the disease, in consequence, apparently, of partaking of food which has been prepared or handled by those having duties about the cholera patient or his linen and bedding."

In the houses of the rich, cholera rarely spreads. "The constant use of the hand-basin and towel, and the fact of the apartments for cooking and eating being distinct from the sick room, are the causes of this."

Cholera once introduced into a building appropriated to pauper children or pauper lunatics, spreads very rapidly. The children and the lunatics are closely packed. At Tooting, two or three children lay in one bed, and vomited over each other. Lunatics are not likely to be more cleanly in their habits. That both the children and the lunatics are, under these circumstances, very liable to swallow some of the cholera ejections, cannot be denied. "Lunatic patients generally suffer in a much greater proportion than the keepers and other attendants."

The mining population have suffered more from cholera than persons in other occupations. There are no privies in the mines. The workmen take food into the mines, and eat with unwashed hands, and without knife and fork.

To show the influence of water as a medium of spreading cholera, Dr. Snow has inquired into the conditions under which several outbreaks of cholera have occurred. "In Albion Terrace, Wandsworth Road, there was an extraordinary mortality from cholera in 1849, which was the more striking as there were no other cases at the time in the immediate neighbourhood." The houses in Albion Terrace are detached a few feet from each other; they are "the genteel suburban dwellings of a number of professionals and tradespeople." On the 26th of July, a storm occurred, the consequence of which was, that a drain burst and inundated the house No. 8, and the adjoining, No. 9, with fetid water. The water broke out of the drain again at No. 8, and overflowed the kitchens, during a heavy rain on August 2nd. The water tanks of all the houses in the terrace were so situated that any impurity getting into one tank would be imparted to the rest. The first cases of cholera in the terrace occurred on July 28. Subsequently more than half the inhabitants of the part of the terrace in which the cholera prevailed were attacked with it.

"There are no data for showing how the disease was communicated to the first patient, at No. 13, on July 28 ; but it was two or three days afterwards, when the evacuations from this patient must have entered the drains having a communication with the water supplied to all the houses, that other persons were attacked, and in two days more the disease prevailed to an alarming extent."

As to the opinion, that the mortality in Albion Terrace was due to the open sewer in Battersea Fields, it suffices to state, that this sewer is 400 feet to the north of the terrace, and that there are several streets and lines of houses, the inhabitants of which suffered scarcely, if at all, quite as much exposed to the emanations from the sewer as are those of Albion Terrace, and, moreover, that there are several houses much nearer to the sewer than the terrace which escaped altogether.

In Charlotte Place, Rotherhithe, are seven houses; the inhabitants of six of these houses obtained their water from a ditch communicating with the Thames, which ditch, moreover, received the contents of the privies of all the seven houses. In these six houses, 25 cases of cholera occurred. The inhabitants of the seventh house obtained their water from a well on their own premises; one case only of cholera occurred in that house.

At Ilford, in Essex, the cholera visited every house but one in a certain row, in the main part of the town. The well used by the inhabitants of the row generally received the refuse which overflowed from the privies. The house in which no cholera happened " was inhabited by a woman who took linen to wash; and she, finding that the water gave the linen an offensive smell, paid a person to fetch water for her from the pump in the town, and this water she used for culinary purposes, as well as for washing."

The terrible outbreak of cholera which lately took place in the neighbourhood of Golden Square, and in which upwards of 500 fatal cases occurred in ten days, Dr. Snow attributes to "some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street." We cannot follow Dr. Snow through all the details he has collected to prove this position. The following facts are among the most striking:—

"Of seventy workmen employed at the brewery of Mr. Huggins, not one had cholera. These men are beer-drinkers, and their master is quite certain that the workmen never obtained water from the pump in the street." There is a deep pump on the premises.

At the percussion-cap manufactory, 37, Broad Street, about 200 workpeople are employed; " two tubs were kept on the premises always supplied with water from the pump in the street, for those to drink who wished;" 18 of these 200 workpeople died of cholera.

At 8 and 9, Broad Street, were 7 workmen employed in the manufactory of dentists' material; they were in the habit of drinking about half-a-pint of the water from the pump once or twice a-day; all seven died of cholera, while two persons who resided constantly on the premises, but did not drink the pump water, only had diarrhoea.

The following is a very remarkable case :—A lady died September 2, of cholera, at West End, Hampstead, a place singularly free from cholera. On inquiry, Dr. Snow found that this lady was in the habit of receiving, by the carrier's cart, a large bottle of water from the pump in Broad Street, as she preferred that water to any other. She received a bottle on August 31, drank of the water that night, and the following day was seized with cholera in the evening, and died on the 2nd September. "A niece, who was on a visit to this lady, also drank of the water; she returned to her residence in a high and healthy part of Islington, was attacked with cholera, and died." Only one other person partook of the water; she did not suffer.

Dr. Snow devotes a considerable part of his work to the consideration of the influence of the water supplied by various Water Companies on the spread of cholera.

Between 1849 and 1853, the Lambeth Water Company removed their waterworks from opposite Hungerford Market to Thames Ditton. During the late outbreak of cholera, the district supplied by this Company suffered much less than in 1849, and much less than the district supplied by the Companies that yet draw their supply from the London section of the Thames. In one of the Southern sub-districts some of the houses are supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company (the water supplied by which is derived from the London section of the Thames) and some by the Lambeth Company. The pipes of each Company go down all the streets and into nearly all the courts and alleys. A few houses are supplied by one, and a few by the other Company; in many cases, a single house has a supply different from that on either side.

"As there is no difference whatever, either in the houses or the people receiving the supply of the two Water Companies, or in any of the physical conditions with which they are surrounded, it is obvious that no experiment could have been devised which would more thoroughly test the effect of water supply on the progress of cholera than this."

Dr. Snow caused an inquiry to be made respecting every death from cholera in a sub-district supplied by these two Companies, from July 8 to August 5. The result was, that, in every 10,000 houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, 71 deaths occurred; while, in the same number of houses supplied by the Lambeth Company, 5 deaths only occurred.

The length at which we have noticed Dr. Snow's work shows the importance we attach to it. We trust that other labourers will enter on the same field, in order that the question he has raised—one of the most important that has ever been raised on the subject—may be absolutely answered. We strongly recommend Dr. Snow's work to the careful perusal of all those interested in the subject of epidemic diseases.

............

Bibliography:

"The first Spasmodic Cholera Epidemic in York, 1832 Issues 37-46"

"The London Medical Gazette: Or, Journal of Medical Practical Medicine, Vol. 9", 1832 - Google eBooks"

"Discuss the history of the understanding of Cholera and measures against it" by MonGenes member, Jeff Coleman 2003

Review of John Snow's work "On the Mode of Communication of Cholera" The Medical Times & Gazette Vol.1; Vol. 10 1855

Wikipedia

Monmouthshire flag by NikNaks

Monmouthshire flag by NikNaks

Flag of St David

Flag of St David

EPIDEMICS & SANITATION

images unless otherwise credited are © MonGenes and may not be reproduced without permission

© MonGenes 2014

EPIDEMICS & SANITATION

A History of Cholera in Britain

Compiled for MonGenes by J. Doe, with additional material by Jeff Coleman:

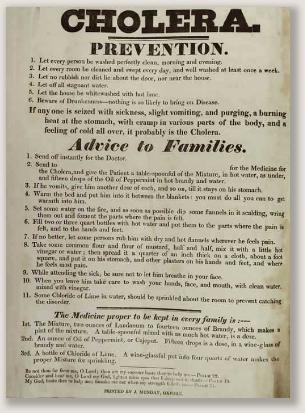

Here is the transcription of the above Cholera Notice

CHOLERA

PREVENTION

1. Let every person be washed perfectly clean, morning and evening

2. Let every room by cleaned and swept every day, and well washed at least once a week

3. Let no rubbish nor dirt lie about the door, nor near the house

4. Let off all stagnant water

5. Let the house be whitewashed with hot lime

6. Beware of Drunkenness - nothing is so likely to bring the Disease

If any one is seized with sickness, slight vomiting, and purging, a burning heat of the stomach, with cramp in various parts of the body, and a feeling of cold all over, it probably is the Cholera.

Advice to Families

1. Send off instantly for the Doctor.

2. Send to ………..….. for the Medicine for the Cholera, and give the Patient a table-spoonful of the Mixture, in hot water, as under, and fifteen drops of the Oil of Peppermint in hot brandy and water.

3. If he vomits, give him another dose of each, and so on, till it stays on his stomach.

4. Warm the bed and put him into it between the blankets: you must do all you can to get warmth into him.

5. Set some water on the fire, and as soon as possible dip some flannels in it scalding, wring them out and foment the parts where the pain is felt.

6. Fill two or three quart bottles with hot water and put them to the parts where the pain is felt, and to the hands and feet.

7. If no better, let some persons rub him with dry and hot flannels wherever he feels the pain.

8. Take some common flour and flour of mustard, half and half, mix it with a little hot vinegar or water; then spread it a quarter of an inch thick on a cloth, about a foot square, and put it ono his stomach, and other plasters on his hands and feet, and where he feels most pain.

9. While attending the sick, be sure not to let him breathe in your face.

10. When you leave him take to wash your hands, face, and mouth, with clean water, mixed with vinegar.

11. Some Chloride of Lime in water, should be sprinkled about the room to prevent catching the disorder.

……

The Medicine proper to be kept in every family is:

1st. The Mixture, two ounces of Laudanum to fourteen ounces of Brandy, which makes a pint of the mixture. A table-spoonful mixed with as much hot water, is a dose.

2nd. An ounce of Oil of Peppermint, or Cajeput. Fifteen drops is a dose, in a wine-glass of Brandy and water.

3rd. A bottle of Chloride of Lime. A wine-glassful put into four quarts of water makes a proper Mixture for sprinkling

……

Be not thou far from me, O Lord; thou art my succour haste thee to help me -

PSALM 22

Consider and hear me, O Lord my God, lighten mine eyes that I sleep not in death - PSALM 13

My God, haste thee to help me; forsake me not when my strength faith me -

PSALM 71

PRINTED BY J. MUNDAY, OXFORD