The Poor Laws,

Monmouthshire Unions

and Workhouses

The Tudor Poor Laws

These were the laws regarding Poor Relief in England around the time of the Tudor Period (1485-1603). The Tudor Poor Laws ended with the passing of the Elizabethan Poor Law in 1601, two years before the end of Elizabeth's reign, a piece of legislation which took the previous Tudor legislation and arranged it into a workable system. During the Tudor period it is estimated that up to a third of the population lived in poverty. The population doubled in size between the reigns of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The closing of the monasteries in the 1530s had increased poverty as the church had previously done much to help the poor.

The Classifications of the Poor as used in the Poor Law system:

This Law had classified people into categories for those considered deserving of poor relief and those who were not considered deserving of poor relief.

Impotent poor could not look after themselves or go to work. They included the ill, the infirm, the elderly, and children with no-one to properly care for them. It was the general opinion that they should be looked after.

Able-bodied poor normally referred to those who were unable to find work – either due to cyclical or long term unemployment in the area, or a lack of skills. Attempts to assist these people, and move them out of this category, varied over the centuries, but usually consisted of relief either in the form of work or money.

Idle poor were of able body but were unwilling to work. They were not considered deserving of poor relief.

Vagrants or beggars, sometimes termed "sturdy rogues", were those who could work but had refused to. Such people were seen in the 16th and 17th centuries as potential criminals, apt to do mischief when hired for the purpose. They were normally seen as people needing punishment, and as such were often whipped in the market place as an example to others, or sometimes sent to Houses of Correction.

The Vagabonds Act 1530 introduced a requirement for a license in order to beg. This meant that only the elderly and disabled could beg and also prevented the able-bodied from begging. In 1536 a more severe law was passed stating that those caught outside of their Parish without work would be punished by being whipped through the streets. If caught a second time they could lose an ear and if caught a third time they could be executed. However officers of the law were reluctant to enforce such a draconian provision.

The Poor Act 1551

This Act required parishes build Workhouses for the poor. In 1552, Registers of the Poor were established and parishes gained the power to raise local taxes through rates. However, help was only available to those considered deserving of poor relief. The deserving poor were those who were willing to work but were unable to find employment as well as those too old, young, or ill to work. Beggars were not considered deserving of poor relief and could be whipped though the town until they altered their behaviour. In 1572 it was made compulsory for all to pay a local Poor Tax; the Poor Act 1575 was introduced making sure that each parish had a store of "wool, hemp, flax, iron" so that the poor could be set to work. The Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 gave all parishes an Overseer of the Poor and the Vagabonds Act 1597 abolished the death penalty for vagrancy. Overseers of the Poor administered Poor Relief such as money, food and clothing. Overseers were often reluctant appointees who were unpaid, working under the supervision of a Justice of the Peace or Magistrate. The law required two Overseers to be elected every Easter, and Churchwardens or Landowners were often selected. The new system of Poor Relief reinforced a sense of social hierarchy and provided a way of controlling the 'lower orders'.

Overseers had four duties:

Estimate how much poor relief money was needed in order to set the Poor Rate accordingly;

Collect the poor rate;

Distribute poor relief; and

Supervise the Poorhouse

Overseers of the Poor were replaced with Boards of Guardians by the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834;, although overseers remained in some places, employed to collect the Poor Rate.

The Poor Relief Act 1601 (43 Eliz 1 c 2)

Popularly known as the "Elizabethan Poor Law", "43rd Elizabeth" or the "Old Poor Law" was passed in 1601 and created a national poor law system for England and Wales. It formalised earlier practices of Poor Relief distribution in England and Wales and is generally considered a refinement of the Act for the Relief of the Poor 1597 that established Overseers of the Poor. The "Old Poor Law" was not one law but a collection of laws passed between the 16th and 18th centuries. The system's administrative unit was the parish. It was not a centralised government policy but a law which made individual parishes responsible for Poor Law legislation. The 1601 act saw a move away from the more obvious forms of punishing paupers under the Tudor system towards methods of "correction".

The 17th Century "House of Correction"

This was a type of establishment built after the passing of the Elizabethan Poor Law 1601, places where those who were "unwilling to work", including vagrants and beggars, were set to work. The building of houses of correction came after the passing of an amendment to the law. However the houses of correction were not considered a part of the Elizabethan Poor Law system because the Act distinguished between settled poor and wandering poor. A notorious magistrate Allan Laing sent three youths to the house of correction for singing in the streets.

The Roundsman System (sometimes termed the billet, ticket, or item system),

In the Elizabethan Poor Law 1601, was a plan by which a Parish paid the occupiers of property to employ the applicants for relief at a rate of wages fixed by the parish. It depended not on the services, but on the wants of the applicants, the employer being repaid out of the poor rate all that he advanced in wages beyond a certain sum. According to this plan the parish in general agreed with a farmer to sell to him the labour of one or more paupers at a certain price, paying to the pauper out of the parish funds the difference between that price and the allowance which the scale, according to the price of bread and the number of his family, awarded him. It received the local name of "billet" or "ticket system" from the ticket signed by the overseer which the pauper in general carried to the farmer as a warrant for his being employed, and afterwards took back to the overseer, signed by the farmer, as a proof that he had fulfilled the conditions of relief. In other cases the parish contracted with a person to have some work performed for him by the paupers at a given price, the parish paying the paupers. In many parishes the roundsman system was conducted by means of an auction, all the unemployed men being put up to sale periodically, sometimes monthly or weekly, at prices varying according to the time of year, the old and infirm selling for less than the able-bodied. The Roundsman system was discontinued by the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834.

Poor Laws after the Tudors

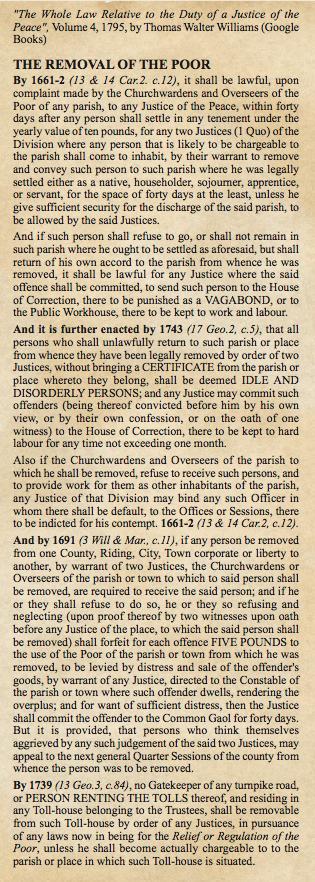

The Poor Relief Act 1662 (14 Car 2 c 12)

It was an Act for the Better Relief of the Poor of this Kingdom and is also known as the Settlement Act or the Settlement and Removal Act. The purpose of the Act was to establish the parish to which a person belonged (i.e. his/her place of "settlement"), and hence clarify which parish was responsible for him should he become in need of Poor Relief (or "chargeable" to the parish poor rates). This was the first occasion when a document proving domicile became statutory: these were called "Settlement Certificates".

After 1662, if a man left his settled parish to move elsewhere, he had to take his Settlement Certificate, which guaranteed that his home parish would pay for his "Removal" costs (from the host parish) back to his home if he needed poor relief. As parishes were often unwilling to issue such certificates people often stayed where they were – knowing that in an emergency they would be entitled to their parish's poor rate.

The 1662 Act stipulated that if a poor person (that is, resident of a tenancy with a taxable value less than £10 per year, who did not fall under the other protected categories) remained in the parish for forty days of undisturbed residency, he could acquire "Settlement Rights" in that parish. However, within those forty days, upon any local complaint, two Justices of the Peace could remove the man and return him to his home parish. As a result, parish elders frequently dispatched their poor to other parishes, with instructions to remain hidden for forty days before revealing themselves. This loophole was closed with the 1685 Act (1 Jam II c.17) which required new arrivals to register with parish authorities. But sympathetic parish officers often hid the registration, and did not reveal the presence of new arrivals until the required residency period was over. As a result, the law was further tightened in 1692 (3 & 4 Will & Mar, c.11), and parish officers were obliged to publicly publish arrival registrations in writing in the local church Sunday circular, and read to the congregation, and that the forty days would only start counting from thereon.

The Settlement Laws benefited the owners of large estates who controlled housing. Some land owners demolished empty housing in order to reduce the population of their lands and prevent people from returning. It was also common to recruit labourers from neighbouring parishes so that they could easily be sacked. Magistrates could order parishes to grant poor relief. However, often the magistrates themselves were landowners and therefore unlikely to make relief orders that would increase poor rates.

The Settlement Act was repealed in 1834 (under the terms of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, which introduced the Union Workhouse, although not fully. The concept of parish settlement has been characterised as "incompatible with the newly developing industrial system", because it hindered internal migration to factory towns. It was finally repealed by Section 245 of, and Schedule 11 to, the Poor Law Act 1927 (c.14) and by the Statute Law Revision Act 1948.

Settlement terms:

To gain settlement in a parish a person had to meet at least one of the following conditions:-

Be born into the parish

Have lived in the parish for forty consecutive days without complaint.

Be hired for over a year and a day that takes place within the parish – (this led to short lengths of hire so that settlement was not obtained).

Hold an office in the parish.

Rent a property worth £10 per year or pay the same in taxes.

Have married into the parish.

Gained poor relief in that parish previously.

Have a seven-year apprenticeship with a settled resident

The Workhouse Test Act 1723

Was also known as the General Act or Knatchbull's Act was Poor Relief Legislation passed by the Government by Sir Edward Knatchbull . The "Workhouse Test" was that a person who wanted to receive poor relief had to enter a workhouse and undertake a set amount of work. The test was intended to prevent irresponsible claims on a parish's Poor Rate. Knatchbull's legislation for Amending the Laws relating to Settlement, Employment and Relief of the Poor marked the first emergence of the workhouse test although this principle was adopted more fully after the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act.

Under the act parishes could provide relief as an individual parish, combine with other parishes or poor relief could be sub-contracted out to those that would feed, clothe and house the poor in return for a weekly rate from the parish.

Between 1723 - 1750, 600 parish Workhouses were built in England and Wales as a direct result of the above Act. The costs of this Indoor Relief was high especially when workhouses were wasteful; this led to the passing of Gilbert's Act in 1782.

The Relief of the Poor Act 1782 (22 Geo.3 c.83),

Also known as Gilbert's Act,was a poor relief law proposed by Thomas Gilbert which aimed to organise poor relief on a County basis, counties being organised into parishes which could set up Workhouses between them. However, these workhouses were intended to help only the elderly, sick and orphaned, not the able-bodied poor. The sick, elderly and infirm were cared for in Poorhouses whereas the able-bodied poor were provided with poor relief in their own homes. Gilbert's Act aimed to be more humane than the previous modification to the Poor Law, the Workhouse Test Act. During the 1780s, there was an increase in unemployment and underemployment due to high food prices, low wages and the effects of enclosing land. This caused poor rates to increase rapidly, which wealthy landowners found unacceptable.

The Act was repealed by the Statute Law Revision Act 1871. Previous attempts to pass legislation - Thomas Gilbert had attempted to pass an act 'for the better Relief and Employment of the Poor' in 1765. Gilbert was a supporter of the Duke of Bedford, which led to his act being blocked by Charles Wentworth, second Marquis of Rockingham. Gilbert tried for 17 years to get his bill passed by Parliament, eventually succeeding during Rockingham's second term as prime minister.

(The above information is taken from Wikipedia)

………………………………………………………………………………………………..

WORKHOUSES

In England and Wales, a Workhouse, colloquially known as a “spike”, was a place where those unable to support themselves were offered accommodation and employment. The earliest known use of the term “workhouse” dates from 1631, in an account by the mayor of Abingdon (Berkshire), reporting that "wee haue erected wthn our borough a workehouse to sett poore people to worke".

The origins of the Workhouse can be traced to the Poor Law Act of 1388, which attempted to address the labour shortages following the Black Death by restricting the movement of labourers, and ultimately led to the state becoming responsible for the support of the poor. But mass unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the introduction of new technology to replace agricultural workers in particular, and a series of bad harvests, meant that by the early 1830s the established system of poor relief was proving to be unsustainable.

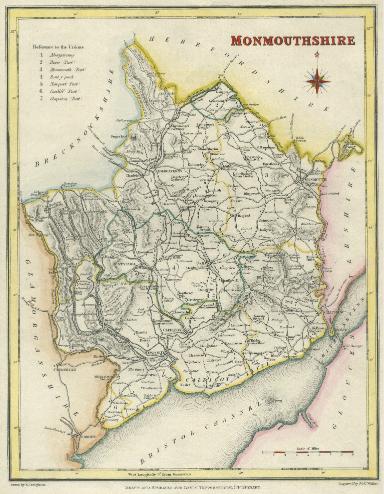

THE MONMOUTHSHIRE POOR LAW UNIONS before 1850

CARDIFF (part)

CHEPSTOW

DORE (part)

MONMOUTH

NEWPORT

PONTYPOOL

The New Poor Law of 1834 attempted to reverse the economic trend by discouraging the provision of relief to anyone who refused to enter a workhouse. Some Poor Law authorities hoped to run workhouses at a profit by utilising the free labour of their inmates, who generally lacked the skills or motivation to compete in the open market. Most were employed on tasks such as breaking stones, bone crushing to produce fertilizer, or picking oakum using a large metal nail known as a spike, perhaps the origin of the workhouse's nickname.

Life in a Workhouse was intended to be harsh, to deter the able-bodied poor and to ensure that only the truly destitute would apply. But in areas such as the provision of free medical care and education for children, neither of which was available to the poor in England living outside workhouses until the early 20th century, workhouse inmates were advantaged over the general population, a dilemma that the Poor Law authorities never managed to reconcile.

Our Searchable Database already contains some Monmouthshire Union Workhouse Birth & Death Records - we will be adding more in due course.

THE SIX MONMOUTHSHIRE POOR LAW UNIONS c.1850

As the 19th century wore on workhouses increasingly became refuges for the elderly, infirm and sick rather than the able-bodied poor, and in 1929 legislation was passed to allow local authorities to take over Workhouse Infirmaries as Municipal Hospitals. Although workhouses were formally abolished by the same legislation in 1930, many continued under their new appellation of Public Assistance Institutions under the control of local authorities. It was not until the National Assistance Act of 1948 that the last vestiges of the Poor Law disappeared, and with them the Workhouses.

The Board of Guardians responsible for the Unions had other duties from time to time, including the registration of births, marriages and deaths, vaccinations, assessments of rates, sanitation, school attendance and infant life protection. By the time of the Local Government Act 1929. Unions were abolished and their duties transferred to County Councils, with responsibility for the poor being transferred to the Public Assistance Committee until 1948.

(Wikipedia)

Below is a link to the lists of available records held at Gwent Archives:

Abergavenny Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6963/cswbga.html

Bedwellty Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6966/cswbgb.html

Chepstow Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6969/cswbgc.html

Monmouth Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6972/cswbgm.html

Newport Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6978/cswbgn.html

Pontypool Board of Guardians Records

http://www.gwentarchives.gov.uk/media/6941/cswbgp.html

Miscellaneous Board of Guardians Records