Monmouthshire flag by NikNaks

Monmouthshire flag by NikNaks

A History of Epidemics in Britain

Compiled for MonGenes by J. Doe, with additional material by Jeff Coleman:

To access this database join

MonGenes Group here:

Flag of St David

Flag of St David

AD 560-590 |

Pestilence in Wales known as Y Fad Velen, or Yellow Fever. |

AD 664 |

Plague similar to the Continental Plague of the previous century - the disease first came to Ireland destroying two thirds of the population and then moved to mainland Britain depopulating southern parts of England before moving on to Northumbria. |

7th-14th Century |

Many famine-related plagues during these centuries which became known as "famine sickness" For example - In the year AD 762, Wales suffered from a pestilence which subsequently spread all over England and continued until AD 771. |

1348 |

The Black Death or The Great Mortality |

1361, 1368, 1369 |

An epidemic of "pestilence" which due to prolonged periods of heat and drought may have been primarily a "famine-sickness". |

1375 |

Epidemic of true bubo-plague countrywide. |

1379 |

Plague in Northern England and London. |

1381-1382 |

A "pestilence" of people, murrain of cattle, failure of crops, great floods, etc. |

1390-91 |

Plague, probably a mixture of famine-pestilence with bubo-plague which was so prolonged and so serious as to be compared with the Great Mortality itself. In 1389, the king was in the south of England, and seeing some of his men prostrated by sudden death, he returned to Windsor. Another outbreak came the year after. Intense heat began in June and lasted until September; great mortality ensued, the epidemic continuing in diverse parts of England, but not everywhere, until Michaelmas; it cut off more young than old, as well as several famous soldiers. The St Albans entry confirms this: “A great plague, especially of youths and children, who died everywhere in towns and villages, in incredible and excessive numbers” After the epidemic there was scarcity, of which we have special accounts from Norfolk. But the heaviest mortality fell in the year 1391. There was first of all a food famine, now in its second year, and aggravated by six weeks of continual gloom in July and August. At the time of the nuts, apples and other fruits of the kind, many poor people died of dysentery, and the sickness would have been worse but for the laudable care of the mayor of London who caused corn to be brought from over sea. At York “eleven thousand” were said to have been buried. Another account says that the North suffered severely, and also the West, and that the sickness lasted all summer. Under the year 1393 many died in Essex in September and October, “on the pestilence setting in.” The next evidence comes from the Rolls of Parliament; in the first parliament of Henry IV. (1399) a petition is presented “that the king would graciously consider the great pestilence which is in the northern parts,” and send sufficient men to defend the Scots marches. |

1405, 1407 |

Plague in the West country, London and East Anglia. In London “thirty thousand men and women” are reported to have died in a short space; and “in country villages the sickness fell so heavily upon the wretched peasants that many homes that had before been gladdened by a numerous family were left almost empty.” |

1413, 1418-1421 |

Plague, various outbreaks. |

1427 |

Influenza epidemic all over England. |

1431 - 1454, 1464-1478 |

Plague, various outbreaks countrywide. |

1478-1479 |

Plague in London, Newcastle, Hull and Southwell. |

1485 |

New disease called "Sweating Sickness"or "The English Sweat" spread all over the entire country. Probably brought over from the Continent by French soldiers recruited by Henry VII for his army around the time of the Battle of Bosworth field in 1485. A manuscript written by a Dr Thomas Forrestier in 1490 tells of this sickness: The sweating sickness, he says, first unfurled its banners in England in the city of London, on the 19th of September, 1485. …. In his later reference of 1490, he says that more than fifteen thousand were cut off in sudden death, as if by the visitation of God, many dying while walking in the streets, without warning and without being confessed. That number of the dead need not be taken as at all exact: nor does it appear whether it is meant for London or for the whole country. But the dramatic suddenness of the attack is illustrated by particular cases in his original treatise of 1485, although deaths so sudden are unheard of in any infection: “We saw two prestys standing togeder and speaking togeder, and we saw both of them dye sodenly. Also in die—proximi we se the wyf of a taylour taken and sodenly dyed. Another yonge man walking by the street fell down sodenly. Also another gentylman ryding out of the cyte [date given] dyed. Also many others the which were long to rehearse we have known that have dyed sodenly.” Gentlemen and gentlewomen, priests, righteous men, merchants, rich and poor, were among the victims of this sudden death. Of the symptoms he says: “And this sickness cometh with a grete swetyng and stynkyng, with rednesse of the face and of all the body, and a contynual thurst, with a grete hete and hedache because of the fumes and venoms.” He mentions also “pricking the brains,” and that “some appear red and yellow, as we have seen many, and in two grete ladies that we saw, the which were sick in all their bodies and they felt grete pricking in their bodies. And some had black spots, as it appeared in our frere (?) Alban, a noble leech on whose soul God havemercy!” |

1487, 1499-1501 |

Plague all over Britain - during 1500-1501 there were 20,000 deaths from plague in London alone (one third of the population). |

1506, 1529, 1563 |

"French pox" as it was called in England (also the great pox and simply the pox), or the Spanish pox, as it was called in France, or the sickness of Naples, or the grandgore). |

1503, 1509-1549 |

Plague, various outbreaks all over the country. |

1514, 1518 |

Earliest known mention of Smallpox in England. |

1518 |

Earliest record of Mezils (Measles) |

1522 |

Outbreaks of Gaol Fever in Cambridge, Oxford. |

1508, 1517 to 1522, 1528 & 1551 |

Further outbreaks of Sweating Sickness. |

1540, 1555-1558 |

Outbreaks of Dysentery, typhus and Influenza all over the country. |

1563 |

The Great Plague of London. From the 1st January to end of December, 17,404 people died of the plague. A proclamation during the London plague of 1563 was directed against cats as well as dogs, “for the avoidance of the plague:” officers were appointed to kill and bury all such as they found at large. Curates and church-wardens were directed to warn the inmates of houses where plague had occurred not to come to church for a certain space thereafter. The blue crosses were to be affixed to infected houses. Also it was ordered by the Mayor and Council that the “filthie dunghill lying in the highway near unto Fynnesburye Courte be removed and carried away; and not to suffer any such donge or fylthe from hensforthe there to be leyde.” On the 9th of July, 1563, plague having been already at work for several weeks, a commission was issued by the queen in Council, that every householder in London should, at seven in the evening, lay out wood and make bonfires in the streets and lanes, to the intent that they should thereby consume the corrupt airs, the fires to be made on three days of the week. On 30th September, 1563, it was ordered that all such houses as were infected should have their doors and windows shut up, and the inmates not to stir out nor suffer any to come to them for forty days. At the same time, a collection was ordered to be made in the churches for the relief of the poor afflicted with the plague, and thus shut up. Another order was that new mould should be laid on the graves of such as die of the plague. Still another, the first of a long series, was to prohibit all interludes and plays during the infection. On the 2nd December, when the deaths had fallen to 178 in the week, an order was issued by the Common Council that houses in which the plague had been were not to be let. On the 20th January, 1564, there was an order for a general airing and cleansing of houses, bedding and the like. By that time the deaths had fallen to 13 in the week. The most rigorous measures in this plague were those which Queen Elizabeth took for her own safety at Windsor in September 1563 - “a gallows was set up in the market-place of Windsor to hang all such as should come there from London. No wares to be brought to, or through, or by Windsor; nor any one on the river by Windsor to carry wood or other stuff to or from London, upon pain of hanging without any judgment; and such people as received any wares out of London into Windsor were turned out of their houses, and their houses shut up”. |

1569-1592 |

23 year Plague period in various parts of the country. |

1580-1582 |

Influenza. |

1586 |

Gaol Fever at Exeter. |

1592-1594 |

The London Plague - 10,662 deaths from the disease in 1593, 421 in 1594; and 29 in 1595. |

1597 |

Plague in the north of England. |

1602-1631 |

Smallpox outbreaks all over the country. |

1638 |

An isolated outbreak of Plague that hit Bedwellty parish in Monmouthshire killed 82 people in 1638, the parish registers revealing a solemn tale of mortality. The diarist Walter Powell in fact wrote that the disease was “very hot in diverse parts of Monmouthshire”. www.walesonline.co.uk |

1641 |

Severe outbreaks of Smallpox & Plague. |

1659-1661 |

Fevers, Agues, Measles and Smallpox in London. |

1603-1666 |

Last period of Plague in England. Deaths from plague in London in the years 1603, 1606 to 1611, 1625, 1636 to38 and 1665 were the greatest in the whole history of the City's epidemics - Population 250,000 there were 30,519 plague deaths in 1603; Population 320,000 - 35,417 deaths in 1625. |

1625 |

Influenza or "Malignant Fever" |

1638-1639 |

“Spotted fever" (not plague). A new disease in England & Wales. In a Hampshire parish "it was raging so fiercely about harvest that there appeared scarce hands enough to take in the corn; which argues, considering there were 2700 parishioners, that 7 might be sick for one that died; whereas of the plague more die than recover. They lay longer sick than is usual in plague,” and there were no plague-tokens. In the very same season (autumn and winter of 1638) we hear of what is obviously the same sickness being epidemic all over the county of Monmouth. On April 23, 1639, the sheriff of Monmouthshire thus explained his delay in executing the king’s writ for an assessment: “In January last I sent forth my warrants for the gathering and levying thereof, but there has been such a general sickness over all this country, called ‘the new disease,’ that they could not possibly be expedited.... Besides, the plague was very hot in divers parts of the county, as Caerleon, Abergavenny, Bedwelty, and many other places. |

1640-1643 |

Smallpox in London. |

1640-1643 |

"War-typhus" in Oxford, Reading &Tiverton. Plague in the provinces. |

1651-52, 1657-59 |

Fever & Influenza. |

1661-65, 1685-86 |

Typhus fever epidemics in London. |

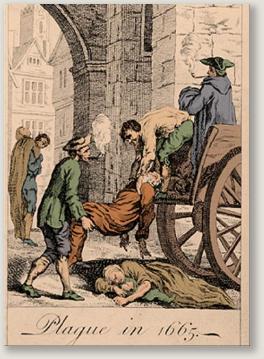

1665 |

Another Great London Plague. Out of a population of 460,000 there were 68,596 (one sixth of London's inhabitants, or 80,000 people - according to Wikipedia) deaths from plague in this year. It is sometimes suggested, as plague epidemics did not recur in London after the fire, that the fire saved lives in the long run by burning down so much unsanitary housing with their rats and their fleas which transmitted the plague. Historians disagree as to whether the fire played a part in preventing subsequent major outbreaks. The Museum of London website claims that there was a connection, while historian Roy Porter points out that the fire left the most insalubrious parts of London, the slum suburbs, untouched. |

1666 |

Small outbreak of Plague in Winchester |

1667 |

The last recorded Plague in England was a solitary epidemic in Nottingham |

1667-78, 1674, 1681, 1694 |

Smallpox epidemics in London. In 1694 Queen Mary II [wife of WilliamIII] died from the disease. |

1697 |

Dysentery - known by contemporaries as The Bloody Flux, was a disease spread by infected food and water, and also by flies. This was a summer disease, more virulent in warm and humid weather, and was especially common in coastal towns and especially ports, introduced by visiting ships whose crew carried the infection. There was a documented outbreak of the disease in Cardiff in 1697. |

1709-20, 1726-29 |

Typhus outbreaks in London |

1710, 1714, 1719 |

Smallpox outbreaks in London |

1721-23 |

Smallpox epidemic. Began in London and during the next 2 years spread extensively. |

1741-42, 1750 |

Typhus epidemics in London. |

1748 |

Diptheria was now identified by Fothergill and described a "sore throat accompanied by ulcers" |

1751-53 |

Smallpox - the most extensive and fatal outbreak in England up to that date. Began in London and rapidly spread to all parts of the country. |

1778 |

Scarlet Fever. |

1796 |

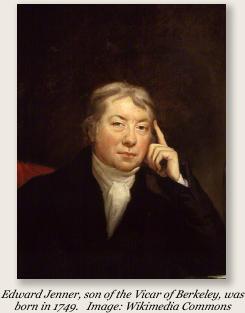

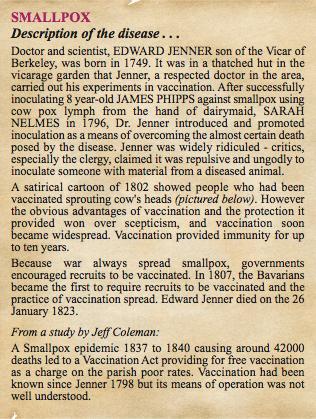

The first Smallpox vaccination was performed by Edward Jenner. |

1816-19 |

Typhus - major outbreak. |

1816-19, 1825-26 |

Smallpox. Two major British epidemics. |

1831-33 |

Cholera spread from the Continent. Outbreaks in 431 towns and villages around Britain. |

1833, 1837, 1847 |

Influenza - widespread epidemics. |

1837-40 |

Smallpox - 42,000 deaths in Britain led to a Vaccination Act providing free vaccination as a charge on the parish poor rates. Vaccination had been known since Jenner in 1798 but its means of operation was not well understood. |

1847-48 |

Typhus - a major outbreak in London. In the autumn of 1848, a number of cases occurred about Bridge Street, Blackfriars; and it was found by Mr. Hutchinson, Surgeon of Farringdon Street, that the well of St. Bride's pump had a communication with the Fleet ditch, up which the tide flows. 'I have a strong impression that many a case of typhoid fever occurring in a respectable neighbourhood has its origin in the water of the neighbouring pump.’ |

1847-67 |

Typhus outbreaks all over Britain especially the North of England and Scotland. |

1848-50 |

Cholera - a widespread epidemic - 52,000 deaths. The disease attacked 803 towns and villages. |

1853-54 |

Cholera - 15,000 deaths. |

1855-57 |

Diptheria - extensive epidemic - many deaths all over the country. (was also known as Croup. Scarletina was often confused with Diphtheria). |

1862-65 |

Typhus epidemic in London - 10,000 deaths. |

1866 |

Localised Cholera outbreak in East London - 5596 deaths; small outbreak in South Wales - 119 deaths |

1870 |

Measles was still a major killer in industrial Wales. In Blaenavon in 1870, a measles outbreak increased the mortality rate from 22 to 166 per 1,000 births and, at its height, six or seven children were dying there every day |

Further notes on some diseases and

the measures employed to eradicate them:

Smallpox

Smallpox was most often a disease of childhood. Surviving it was almost a rite of passage for children, but recovery, though it gave immunity from further infection, often left the sufferer horribly scarred. Smallpox also came with great social stigma, leaving scarred survivors ostracised from their friends and families. It could run rampant through families and communities and, in the days before inoculation, there was little defence. So feared was it that advertisements for servants in 18th century households sometimes stipulated that applicants must already have had the disease, to prevent them bringing the infection into a family.

BUBONIC PLAGUE in Wales

Wales suffered less from the ravages of the plague than other parts of Britain. Bubonic plague was less virulent at the higher altitudes and colder environments found in Wales. Also, with large expanses of the Welsh countryside sparsely populated and fewer large towns in Wales, it made it more difficult for the disease to establish itself. The exception to this was the welsh coastline. With over a hundred miles of coast, and many large and small ports, there was ample opportunity for the introduction of disease and it was the port towns, and also towns along rivers and trading routes, which were the worst hit.

VARIOLATION or INNOCULATION against Smallpox in the 19th Century

Variolation or Inoculation was the method first used to immunise against smallpox (Variola) with material taken from a patient or a recently variolated individual in the hope that a mild but protective infection would result. The procedure was most commonly carried out by inserting or rubbing powdered smallpox scabs or fluid from pustules into superficial scratches made in the skin. The patient would develop pustules identical to those caused by naturally occurring smallpox, usually producing a less severe disease than naturally-acquired smallpox. Eventually, after about two to four weeks, these symptoms would subside, indicating successful recovery and immunity

VACCINATION

The 1840 Public Health Act made variolation illegal and it provided optional vaccination, free of charge.

In general, the disadvantages of variolation are the same as those of vaccination, but added to them is the generally agreement that variolation was always more dangerous than vaccination. In March of 1842 at Abergavenny, there were four cases of Workhouse babies dying after having been vaccinated for smallpox.

The introduction of inoculations for smallpox, cowpox and measles was adopted swiftly in many areas of Wales. Vaccination was first made compulsory with the 1853 Public Health Act, and the provisions were made more stringent in 1867, 1871, and 1874. But not everyone believed in vaccination: In Newport, some parents argued against the safety of the vaccinations, and were in fact prosecuted for refusing to present their children according to the requirements of the Vaccination Acts. On July 31, 1869, the Western Mail reported on a conference about vaccination held in Cardiff, at which a certain Dr Haviland reported his disgust at seeing children forcefully injected even in the waiting rooms of railway stations by over-zealous overseers. The case for the success of vaccination, he argued, was unproven.

Was it DYSENTERY or CHOLERA?

A report in The Morning Chronicle, in the month of August 1832:

"EXTRAORDINARY CIRCUMSTANCES"

On Tuesday, the 9th inst., as six of the reapers employed by Thomas Hughes, Esq., near Grosmont, in this county, were reaping, they found themselves suddenly covered with swarms of insects, very like the common small ant, and with wings. They became so troublesome that they took their clothes off for the purpose of shaking them off, but they could not get rid of them; as, whenever they settled, the animalcule never attempted to fly again. Immediately after, all the men were attacked with violent sickness and diarrhoea, and were obliged to discontinue working. Four of them recovered, with the assistance of some medicine administered by their master, and were enabled to work again the following day; the other two, who were more violently affected, had medical advice, but did not recover for three or four days sufficiently to work. The men had eaten nothing but good plain food. Mr. Hughes, who was with his reapers at the time, but did not then feel unwell, during the night had himself a slight attack of the same nature. - [The correspondent who has favoured us with the above singular fact, on the accuracy of whose statement we have complete reliance, mentions that a species of fly, before unknown, has appeared in many places visited by cholera. Ed., Monmouthshire Merlin]

Bibliography:

"The Pestilence in England: an Historical Sketch" by John Netten Radcliffe (Google eBooks)

"Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present" by George C. Kohn (Google eBooks)

"Discuss the history of the understanding of Cholera and measures against it" by MonGenes member, Jeff Coleman 2003

"History of disease in Wales" - http://www.walesonline.co;

Abergavenny St Mary's Burial Register 1837-1845

Wikipedia

EPIDEMICS & SANITATION